Por Rosalba Esquivel Cote

Click here for English version

Abro un ojo, y luego el otro, ya amaneció, la noche pasó rápido, sigo bostezando, me tallo los ojos.

Me alegra poder seguir acurrucada entre las sábanas blancas de algodón que visten mi cama.

Y esa cobija azul cada vez más deshilachada que hace 20 años mi mamá me compró en Chiconcuac.

Sin duda me siento bendecida, afortunada … inmensamente feliz por ese momento envidiable.

No lo puedo evitar, curiosa, me levanto a mirar por la ventana, ha pasado la ventisca.

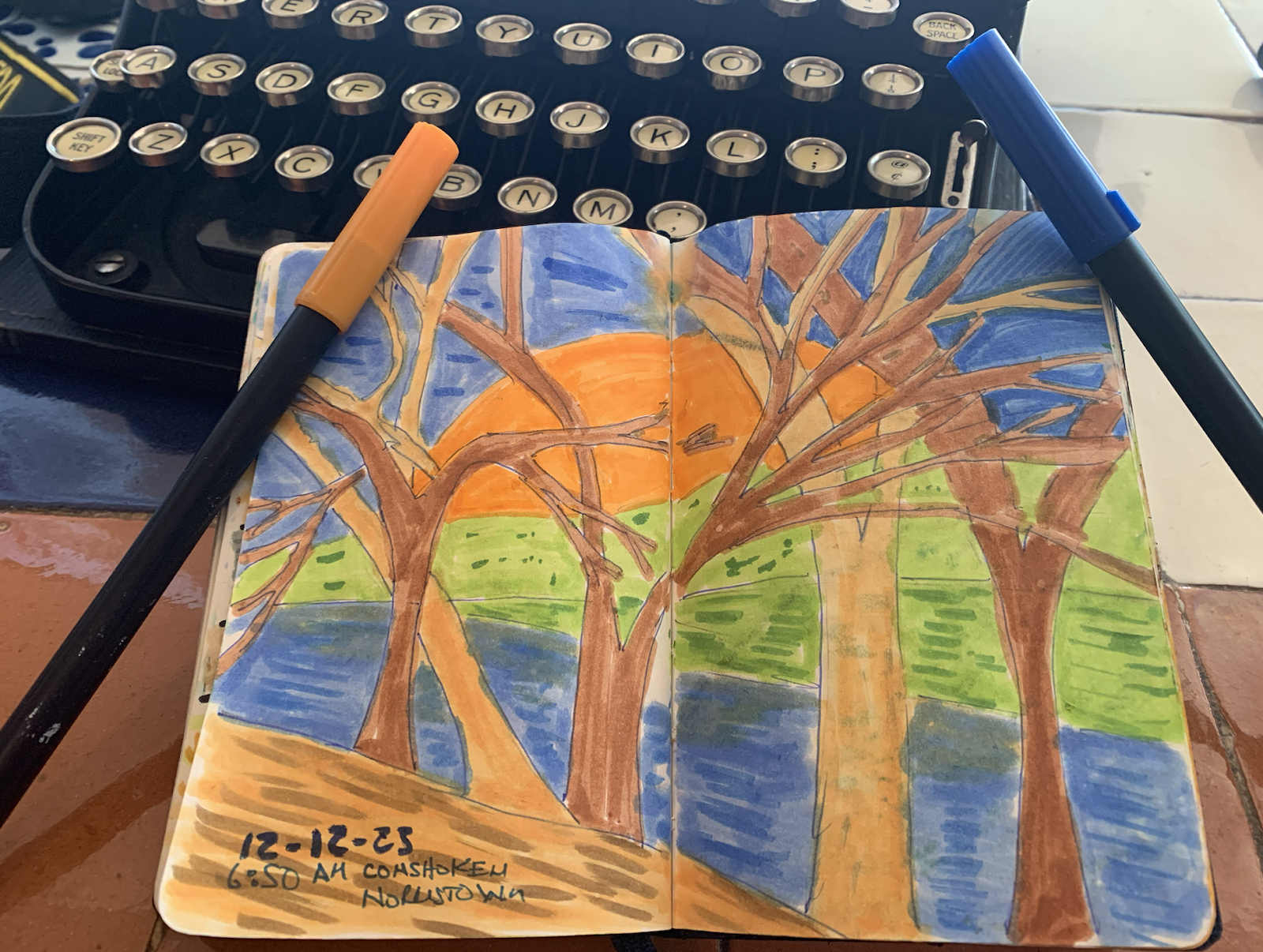

Veo por el vidrio empañado la luz del día cada vez más intensa que se asoma por detrás del vecindario.

El cielo es azul claro, en este momento se ilumina con tonos intensos de rojos, amarillos y anaranjados.

Como colores del telón que precede la presencia del sol. Una vistosa introducción al día que nace.

Resplandeciente, pero no más que la luz que lastima reflejada por el suelo cubierto por la nada.

Tras la borrasca un montón de nieve y hielo se han acumulado en el patio, en la calle y en el parque.

No distingo los cedros tan bien cuidados del vecino, ni siquiera veo dónde comienza la banqueta.

Siento frío, y el espectáculo del amanecer muestra un desierto blanco de areniscas de cristal.

Algunos arces erguidos en varas se mueven a voluntad de la fuerza del viento.

El panorama me hace sentir más frío, pero no por la falta de calor, sino frío de sentimiento.

Como de tristeza, como de nostalgia, como de ansiedad. El tiempo pasó, se fue.

No tengo ganas de salir, prefiero quedarme quieta y sentada en mi sillón afelpado.

Dentro de mi pijama de franela roja decorada con renos, y mis calcetines de rayitas.

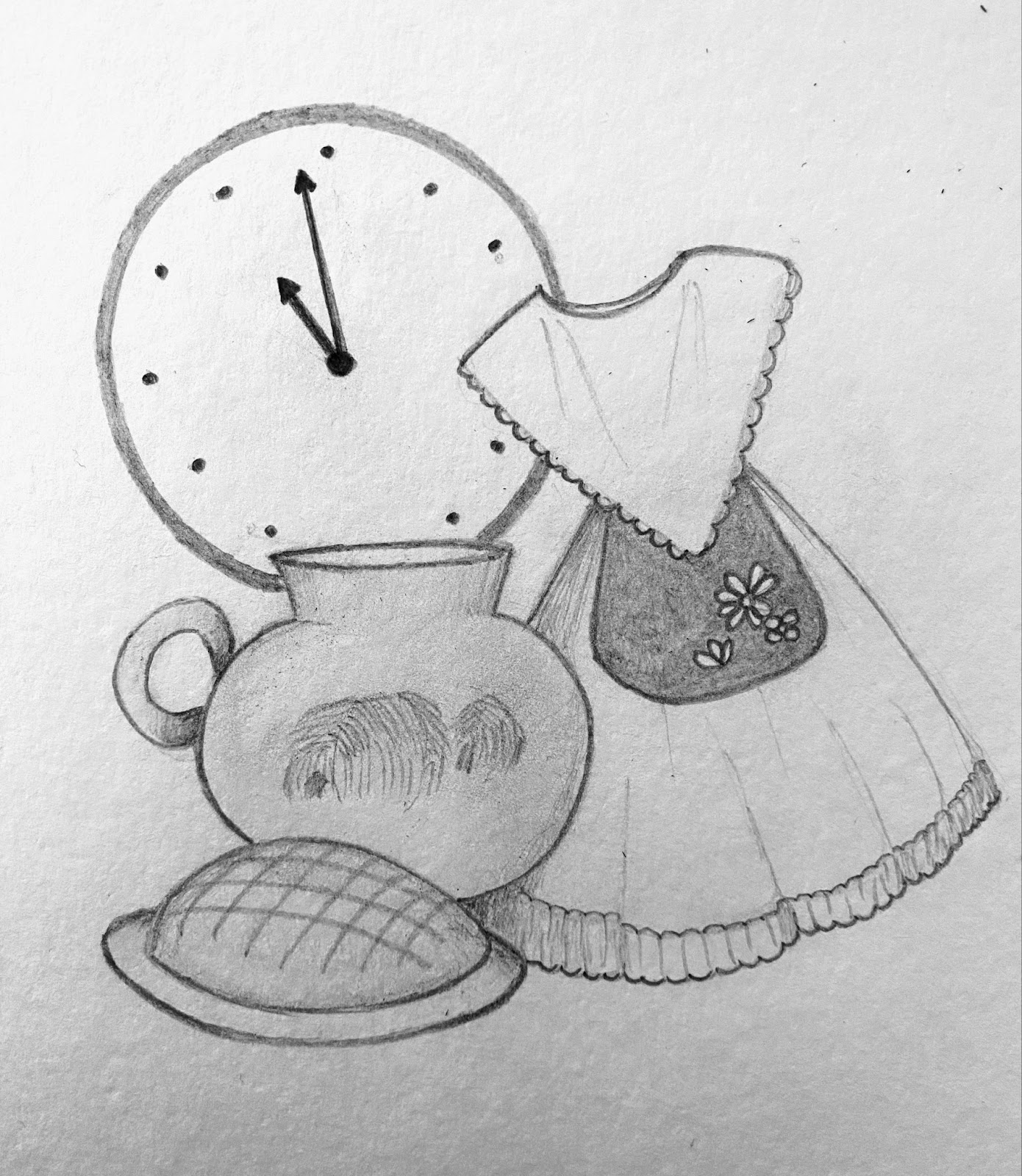

Sí, también abrigada con esa cobija elaborada por artesanos del Estado de México con olor a mi cama.

Bebiendo a sorbos un chocolate “Abuelita” bien calientito, y rebanadas de bolillo tostadito.

Y que mejor, acompañada de Carlos Fuentes, de Gabriel García Márquez o de Isabel Allende.

En uno de esos sorbos levanto la cabeza para tratar de sorprender al cuervo que para en la ventana.

No lo veo, lo único que miro es el paisaje liso y misterioso, que no me deja de sorprender.

¿En qué momento llegué hasta aquí?, si todavía puedo oler al pasto recién podado.

Abejas rondando las flores de mi jardín, Zorzales petirrojos persiguiéndose en busca de pareja.

El sol radiante, la playa con visitantes acalorados, los días eternos y las noches tan cortas.

Mi playera decorada con un cianotipo, mis pantalones cortos de mezclilla y mis sandalias de cuero.

Qué rápido desfiló el viento, la caída de las hojas, los hermosos atardeceres escarlatas y bermellones.

Las caminatas de la gente, las reuniones familiares los fines de semana alrededor del barbiquiu.

Las risas, los perros corriendo tras los frizbies, los niños embarrados de tierra y de helado.

¿Dónde quedó todo eso, dónde quedó esa vida?

Disfruté de cada estación, de cada momento, de cada respiro, de cada parpadeo.

Cierro los ojos y comienzo a recordar. Recordar significa viví, que estuve ahí.

Sigo aquí para experimentar aún más, para ver más, para saber más, para vivir más.

Lo he decidido. No me queda más que vestirme para la ocasión.

Acompañan a mi invernal atavío mi bufanda y mi gorro que tejí con las Artivistas.

Salgo a disfrutar, salgo a vivir el invierno, porque así la vida.

La vida marcha implacable, la vida no para, la vida no espera.

Pero la vida da suficiente tiempo. Tiempo para aprender, para equivocarse y para volver a empezar.

La vida te toca a cada segundo. La vida viene al inhalar y se va al exhalar, así, así de rápido.

Y salgo a vivir, a vivir el invierno.

English Version:

WINTER

By Rosalba Esquivel Cote

I open one eye, and then the other, it’s already dawn, the night passes quickly, I keep yawning, I scratch my eyes.

I’m glad I can continue snuggling between the white cotton sheets that dress my bed.

And that increasingly frayed blue blanket that my mother bought me in Chiconcuac 20 years ago.

Without a doubt I feel blessed, lucky… immensely happy for that enviable moment.

I can’t help it, curious, I get up to look out the window, the blizzard has passed.

I see through the fogged glass the increasingly intense daylight peeking out from behind the neighborhood.

The sky is light blue, at this time it is illuminated with intense tones of reds, yellows and oranges.

Like colors of the curtain that precedes the presence of the sun. A colorful introduction to the day that is born.

Resplendent, but no more than the painful light reflected by the ground covered in nothingness.

After the storm, a lot of snow and ice have accumulated in the yard, on the street and in the park.

I can’t tell the well-kept cedar trees from the neighbor’s, I don’t even see where the sidewalk begins.

I feel cold, and the spectacle of dawn shows a white desert of crystal sandstones.

Some maples standing on poles move at the whim of the wind.

The panorama makes me feel colder, but not because of the lack of heat, but rather the coldness of feeling.

As of sadness, as of nostalgia, as of anxiety. Time passed, it left.

I don’t feel like going out, I prefer to stay still and sit in my plush chair.

Inside my red flannel pajamas decorated with reindeer, and my striped socks.

Yes, also warm with that blanket made by artisans from the State of Mexico that smells like my bed.

Sipping a very warm “Abuelita” chocolate, and slices of toasted bolillo.

And what better, accompanied by Carlos Fuentes, Gabriel García Márquez e Isabel Allende.

In one of those sips I raise my head to try to surprise the crow that stops at the window.

I don’t see it, the only thing I look at is the smooth and mysterious landscape, which never ceases to surprise me.

When did I get here? I can still smell the freshly mowed grass.Bees prowling the flowers in my garden, Robin Thrushes chasing each other in search of a mate.

The radiant sun, the beach with hot visitors, the eternal days and the very short nights.

My t-shirt is decorated with a blueprint, my jean shorts and my leather sandals.

How quickly the wind passed, the falling leaves, the beautiful scarlet and vermilion sunsets.

People’s walks, family gatherings on weekends around the barbiquiu.

The laughter, the dogs running after the frisbees, the children muddy with dirt and ice cream.

Where was all that, where was that life?

I enjoyed every season, every moment, every breath, every blink.

I close my eyes and begin to remember. Remembering means I lived, that I was there.

I’m still here to experience even more, to see more, to know more, to live more.

I have decided. I have nothing left but to dress for the occasion.

Accompanying my winter outfit are my scarf and my hat that I knitted with the Artivistas.

I go out to enjoy, I go out to live the winter, because that’s life.

Life marches relentlessly, life doesn’t stop, life doesn’t wait.

But life gives enough time. Time to learn, to make mistakes and to start again.

Life touches you every second. Life comes when you inhale and goes when you exhale, just like that, just like that.

And I go out to live, to live the winter.

Rosalba Esquivel Cote

She is a woman, Mexican, microbiologist, teacher, apprentice, and artist. “Let your cries be read!”

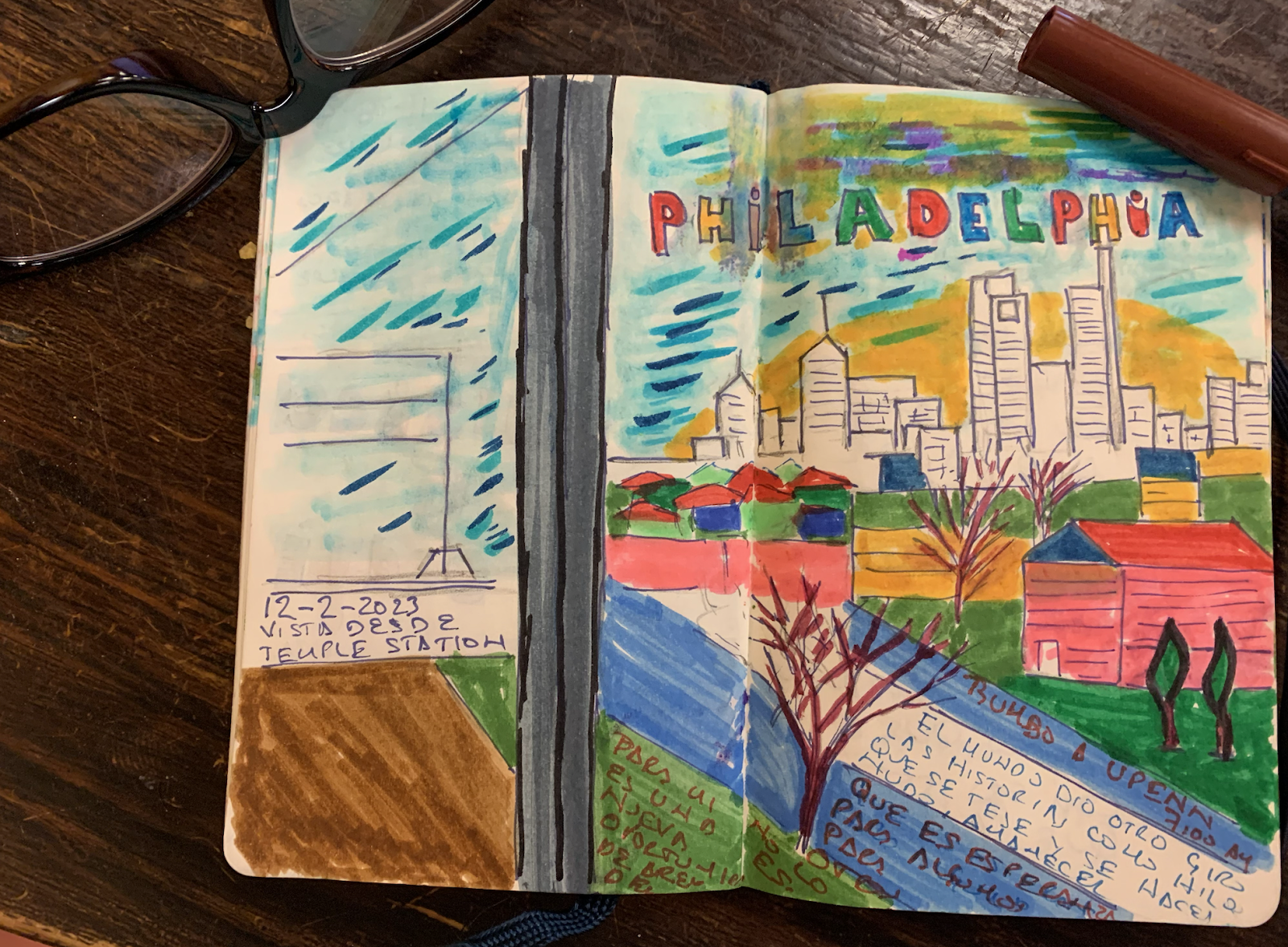

Selected Works by Rosalba Esquivel Cote:

La máquina de coser de mamá (III)

La máquina de coser de mamá (II)

La Máquina De Coser De Mamá (I)

Mi Amiga y La Medusa

Otoño