Por Rosalba Esquivel Cote

Click here for English version

III. CAPÍTULO TRES. Tic, Trabajando, Toc, Recordando

El reloj seguía su marcha, tic, toc, tic, toc.

Tic

Tic, Kate ensartaba con destreza las agujas de la máquina de coser, organizando las piezas de tela que comenzaba a zurcir. Las primeras faldas de organza blanca con ondulados holanes de encaje comenzaban a salir de aquel artefacto como si fueran cadenas. Rose, apuradamente separaba las faldas con unas tijeras pequeñas. Una a una como si fueran tortillas recién salidas de la tortilladora las colocaba sobre una mesita cerca de la máquina de coser. Pronto, una montaña de faldas se levantaba desde el suelo para ser desprendidas por la niña.

Toc, el ruido de la máquina se escuchaba desde la calle, que parecía aún desierta. Era una noche serena, el ruido de uno que otro auto que circulaba por ahí competía con el de la máquina de coser. “¡Ahora las blusas!”, exclamó Kate, con evidente excitación y cansancio. Rodri tosía nuevamente, la madre que recogía los cortes de las blusas y las mangas lo alcanzó a escuchar. Kate se dirigió apurada para atenderlo, las flemas en el pecho del niño le provocaban tal agitación. Ella se dirigió a la cocina para preparar un poco de té con hojas de eucalipto, remedio que en ocasiones ayudaba al niño a expulsar sus males. Listo, Rodri quedó dormido nuevamente.

Tic, “¿cómo estará Jorch?, ¿qué problema habrá pasado en la fábrica que lo habrá obligado a trabajar hasta tarde? ¿cómo la estará pasando?”, la mujer quedó pensativa un rato, y al ver al niño dormir tranquilamente, regresó a su lugar de trabajo. La pequeña Rose terminaba de acomodar las faldas, pero ya más lento; el cansancio y el sueño la estaba venciendo. No obstante, hacía esfuerzos por mantenerse despierta; “mamá, cuéntame cómo te enamoraste de mi papá”, dijo animada. Una leve sonrisa esbozó el rostro de Kate. Mientras unía los cortes de tela para formar las blusas de esos benditos vestiditos, la madre comenzó a recordar. Y para ayudar a mantener despierta a su hija, comenzó a platicar su historia con el ruido del motor como fondo musical.

Toc

Toc, “Verás, cuando yo tenía 16 años”, recordó Kate, “trabajaba en una fábrica donde se confeccionaban pantalones de mezclilla. Mi amiga Silvia, quien era novia de mi primo Toño, me llevó ahí. En ese lugar conocí a tu papá”. “¿Silvia?, ¿Mi tía Silvia?”, interrumpió la niña. “No sabía que fueron amigas desde hace mucho tiempo”. “Sí”, contestó su madre. “Ella y yo siempre hemos sido grandes amigas”.

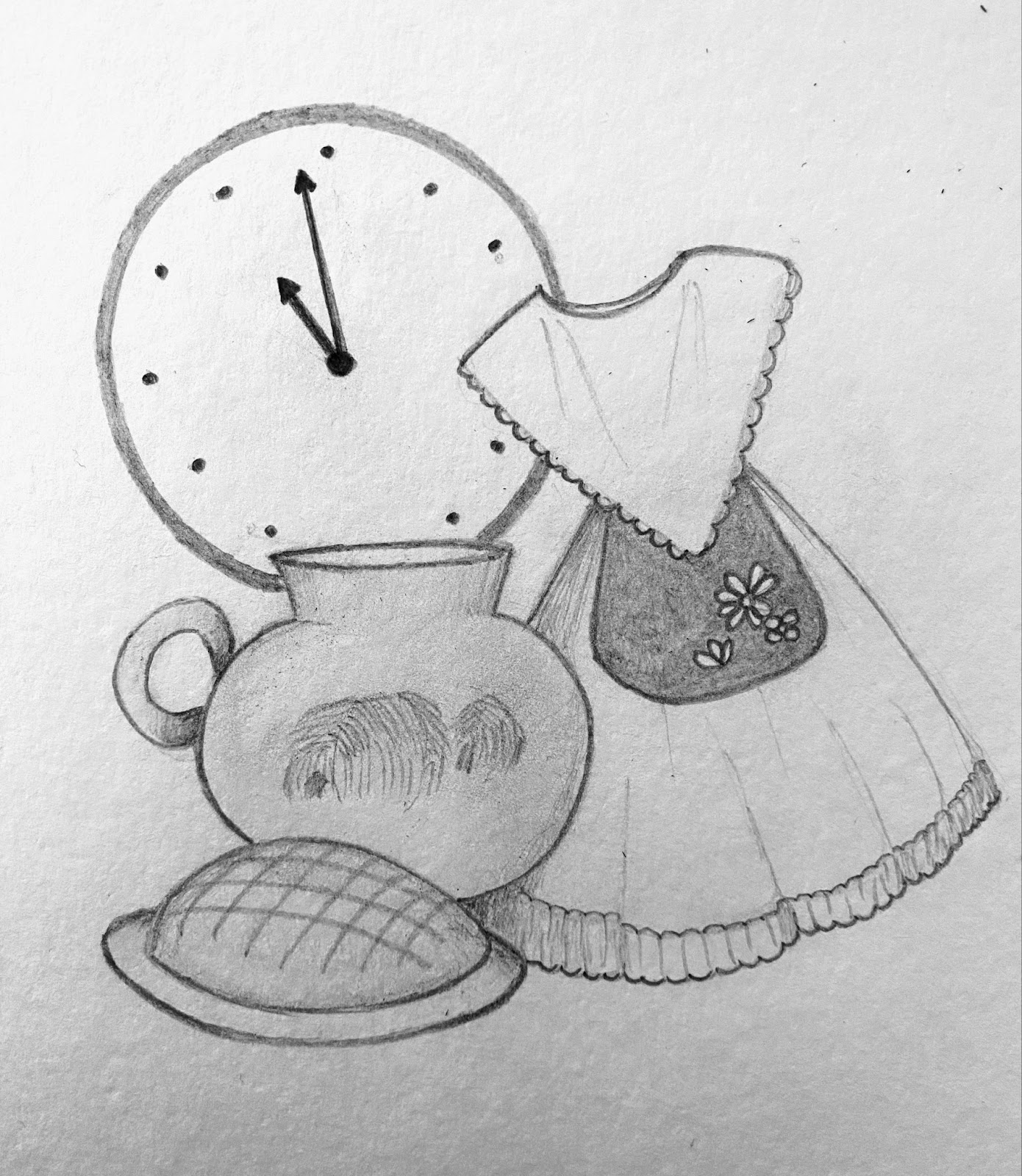

Tic, y la madre comenzó a hablar mientras sus pies se movían al son que las manos colocaban las telas sobre la máquina de coser, y al ritmo de los engranajes. “Nosotras nos conocimos desde que éramos niñas. Ella vivía en una casa cerca de la mía; su mamá Doña Lupita, era una señora robusta pero ágil, siempre andaba vestida de falda y blusa, ambas cubiertas con un delantal de tela de cuadritos y flores bordadas de diferentes colores. La señora era muy amable pero enérgica a la vez. Lo que más me gustaba de ella era que todos los días había comida abundante y caliente en su casa, a diferencia de la mía, donde pocas veces había comida preparada para comer”.

Toc, “Mi familia era muy humilde. Mi mamá trabajaba mucho durante el día, y por las mañanas me daba pena despertarla. Así que casi nunca se encontraba despierta antes de que yo me fuera a la escuela. En la cocina pocas veces encontraba algo para desayunar o para hacerme una torta. Y la verdad, como casi siempre, se me hacía tarde para ir a la escuela, no me daba tiempo de buscar algo. A mis nueve años yo tenía que ver que mi hermanita, de meses de nacida, tuviera un biberón listo y el pañal cambiado antes de salir de casa. Muchas veces me arrepentía de no llevar algo que comer porque a la hora del recreo mi estómago sonaba mucho por el hambre que tenía. En ocasiones, Silvia me convidaba de su almuerzo, ella siempre traía una manzana partida en cuatro, un bolillo relleno de frijoles chinitos y queso, y traía una cantimplora con agua de limón”.

Tic, “Un día, Silvia me pidió pasar por ella a su casa porque llevaría mucho material a la escuela. Yo acepté y al otro día tempranito pasé por ella. Muy amable Doña Lupita me hizo pasar y en lo que esperaba a Silvia, me ofreció un tecito de canela y un pan de dulce, ¡oh, qué delicia!, el aroma de ese té era fenomenal. Yo escogí una concha de vainilla para remojar en el tan preciado líquido calientito, y cuando lo llevé a mi boca para morderlo, la sensación fue de total placer. Nunca había sentido esa sensación de placer, satisfaciendo mi hambre con ese singular manjar. Cerré los ojos y me dejé llevar por el aroma y el sabor. En ese momento descubrí lo que era ser feliz: así, un jarro de panza gorda y cuello corto y ancho, hecho de barro rojo, decorado con el dibujo de unas casitas de paja. El calorcito que sentí al tocarlo con mis dos manos recorrió todo mi cuerpo, haciéndome olvidar el frío que sentía a esas horas por la mañana, y todo ello acompañado de lo mejor: un grande, atractivo y esponjadito pan, una concha decorada con azúcar amarilla, con un aroma a vainilla que se confundía con la de la canela, puesto en un plato también de barro. En ese momento sentí estar en la gloria, sentí amor por la bondad de aquella dulce mujer. Y sintiéndome culpable, desee que fuera mi mamá”.

Toc, “imaginé, si Doña Lupita fuera mi mamá, yo vestiría un uniforme perfecto, con una chazarilla blanca impecablemente planchada, con el jumper de cuadritos verdes y azules, limpio oliendo a jabón de lavandería igual que el suéter de acrilán, y mis zapatos, unos zapatos negros brillantes sin raspones. Yo me esmeraría siempre en mantenerlos así, tal vez yo le pondría unos plásticos en las suelas para que no se ensuciaran con el lodo de la calle, y para no gastarlos. Mis pies siempre irían calientitos con calcetas de algodón, cubriendo mis pies y mis pantorrillas, mis piernas se verían como dos columnas, altas, imponentes, como si fueran la base de un monumento, de una obra de arte: yo. Mi mamá Lupita me peinaría suavemente con un cepillo de cerdas rosas, y me haría unas trenzas perfectas, adornadas con unos adorables moños de satín rojo. Mi cara no sólo la lavaría con jabón, sino que le pondría esa crema perfumada de rosas que tanto me gusta oler cuando saludo a mi amiga. Yo desayunaría tecito de canela y pan de dulce todos los días, yo… yo sería feliz todos los días. Yo sería feliz. Yo sería feliz”.

Tic, de pronto, una mano me sacudió diciéndome, “Kate, despierta, termina tu canela, Silvia ya está aquí, se les va a hacer tarde”. Yo abrí los ojos, y me miré ahí, sentada frente a mi desayuno a punto de terminar. Había imaginado un sueño, un dulce sueño. Yo creo que Doña Lupita me vio tan emocionada que me dijo “hija, si quieres, puedes pasar por Silvia todos los días y si gustas. Te serviré una canela con pan”. Yo la miré llena de agradecimiento, y acepté su invitación. A partir de ese día, al menos mientras desayunaba en casa de Silvia, Doña Lupita era mi mamá”. Los ojos de Kate se llenaron de emoción, parecían el fondo de un pozo donde se distinguía el reflejo de la luna llena sobre el agua cristalina. Se pasó la manga de su suéter de acrilán sobre su cara para secar sus ojos, quedó callada y siguió cosiendo. En tanto, Rose, no supo que decir, sintió un nudo en la garganta, era obvio que la infancia de su madre no había sido buena. Cómo deseó la niña, en ese momento, tener el poder de regresar el tiempo y cambiar la vida de Kate.

Toc, Rose entendió que la vida no es justa para todos, y que es una cuestión de “suerte” el nacer con ciertos padres, en un lugar y en un tiempo determinados. Y ella agradecía que Kate fuera su mamá. Una mujer valiente y amorosa. Y para romper ese conmovedor momento, la niña preguntó en un dejo de burla quejosa. “Pero mamá, se te olvidó decirme cómo te enamoraste de mi papá”. Kate levantó la cara, miró a su hija, y ambas comenzaron a reír. Y se dieron cuenta que las carcajadas se escucharon más alto, el ruido de la calle había casi desaparecido. Kate y Rose, siguieron trabajando en medio de risa y recuerdos con el “traca-traca” de la máquina de coser.

Tic, toc, tic, toc.

English Version:

Mom’s Sewing Machine

III. CHAPTER THREE. Tick, Working, Tock, Remembering

The clock kept ticking, tick, tock, tick, tock.

Tick

Tick. Kate deftly threaded the needles of the sewing machine, organizing the pieces of fabric she began to darn. The first white organza skirts with wavy lace ruffles began to emerge from that device as if they were chains. Rose hurriedly separated the skirts with small scissors. One by one, as if they were tortillas fresh from the tortilla maker, he placed them on a small table near the sewing machine. Soon, a mountain of skirts rose from the ground to be removed by the girl.

Tock. The noise of the machine could be heard from the street, which still seemed deserted. It was a quiet night, the noise of the occasional car driving by competed with that of the sewing machine. “Now the blouses!” Kate exclaimed, with obvious excitement and fatigue. Rodri coughed again, the mother who was collecting the cuts of the blouses and sleeves could hear him. Kate hurried to attend to him, the phlegm in the boy’s chest causing him such agitation. She went to the kitchen to prepare some tea with eucalyptus leaves, a remedy that sometimes helped the child expel his illnesses. Ready, Rodri fell asleep again.

Tick. “How is Jorch? What problem has happened at the factory that has forced him to work late? How is he doing?” The woman was thoughtful for a while, and when she saw the child sleeping peacefully, she returned to her workplace. Little Rose finished arranging her skirts, but slower; tiredness and sleep were overcoming her. However, she tried to stay awake; “Mom, tell me how you fell in love with my dad”, she said excitedly. A slight smile appeared on Kate’s face. While she was joining the cuts of fabric to form the blouses of those blessed little dresses, the mother began to remember. And to help keep her daughter awake, she began to talk about her story with the sound of the engine as a musical background.

Tock

Tock. “You see, when I was 16”, Kate recalled, “I worked in a factory where jeans were made. My friend Silvia, who was my cousin Toño’s girlfriend, took me there. In that place I met your dad”. “Silvia? My aunt Silvia?” the girl interrupted. “I didn’t know they were friends for a long time”. “Yes”, his mother answered. “She and I have always been great friends”.

Tick, and the mother began to speak while her feet moved to the sound of the hands placing the fabrics on the sewing machine, and to the rhythm of the gears. “We have known each other since we were children. She lived in a house near mine; his mother, Doña Lupita, was a robust but agile lady, she was always dressed in a skirt and blouse, both covered with an apron made of checkered fabric and embroidered flowers of different colors. The lady was very kind but energetic at the same time. What I liked most about her was that every day there was abundant, hot food in her house, unlike mine, where there was rarely food prepared to eat”.

Tock. “My family was very humble. My mother worked a lot during the day, and in the mornings, I was sad to wake her up. So, she was almost never awake before I left for school. In the kitchen I rarely found something for breakfast or to make a cake. And the truth is, as almost always, I was late to school, I didn’t have time to look for something. At nine years old, I had to make sure my little sister, who was only a few months old, had a bottle ready and her diaper changed before leaving the house. Many times, I regretted not bringing something to eat because at recess time my stomach was very hungry because of how hungry I was. Sometimes, Silvia would treat me to her lunch, she always brought an apple cut into four, a bolillo filled with ‘chinitos’ beans and cheese, and she brought a canteen with lemon water”.

Tick. “One day, Silvia asked me to pick her up at her house because she would be bringing a lot of material to school. I accepted and picked her up early the next day. Very kind Doña Lupita let me in and while I was waiting for Silvia, she offered me a little cinnamon tea and a sweet bread, oh, what a delight! The aroma of that tea was phenomenal. I chose a vanilla shell to soak in the precious warm liquid, and when I put it in my mouth to bite it, the sensation was one of total pleasure. I had never felt that sensation of pleasure, satisfying my hunger with that unique delicacy. I closed my eyes and let myself be carried away by the aroma and flavor. At that moment I discovered what it meant to be happy: like this, a jug with a fat belly and a short, wide neck, made of red clay, decorated with the drawing of some straw houses. The warmth I felt when I touched it with my two hands ran through my entire body, making me forget the cold I felt at that time of the morning, and all of this accompanied by the best: a large, attractive and fluffy bread, a shell decorated with yellow sugar. , with a vanilla aroma that was confused with that of cinnamon, placed in a clay dish. In that moment I felt like I was in glory, I felt love for the kindness of that sweet woman. And feeling guilty, I wished she were my mother”.

Tock. “I imagined, if Doña Lupita were my mother, I would wear a perfect uniform, with an impeccably ironed white jacket, with the jumper with green and blue squares, clean and smelling of laundry soap like the acrylic sweater, and my shoes, shiny black shoes without scratches. I would always try to keep them like this, maybe I would put some plastic on the soles so that they wouldn’t get dirty with the mud from the street, and so as not to wear them out. My feet would always be warm with cotton socks, covering my feet and my calves, my legs would look like two columns, tall, imposing, as if they were the base of a monument, of a work of art: me. My mom Lupita would comb my hair gently with a pink bristle brush, and she would make me perfect braids, adorned with adorable red satin bows. I would not only wash my face with soap, but I would put that rose-scented cream on it that I like to smell so much when I greet my friend. I would have cinnamon tea and sweet bread for breakfast every day, I… I would be happy every day. I would be happy. I would be happy”.

Tick. Suddenly, a hand shook me telling me, “Kate, wake up, finish your cinnamon tea, Silvia is already here, they’re going to be late”. I opened my eyes, and looked at myself there, sitting in front of my breakfast about to finish. I had imagined a dream, a sweet dream. I think that Doña Lupita saw me so excited that she told me “Kate, if you want, you can stop by Silvia every day if you like. I will serve you a tea cinnamon with bread”. I looked at her full of gratitude and accepted her invitation. From that day on, at least while I was having breakfast at Silvia’s house, Doña Lupita was my mother”. Kate’s eyes were filled with emotion, they looked like the bottom of a well where the reflection of the full moon could be seen on the crystal-clear water. She passed the sleeve of her acrylic sweater over her face to dry her eyes, remained silent and continued sewing. Meanwhile, Rose didn’t know what to say, she felt a lump in her throat, it was obvious that her mother’s childhood had not been good. How the girl wished, at that moment, that she had the power to turn back time and change Kate’s life.

Tock. Rose understood that life is not fair for everyone, and that it is a matter of “luck” to be born with certain parents, in a certain place and at a certain time. And she was grateful that Kate was her mother. A brave and loving woman. And to break that moving moment, the girl asked in a hint of plaintive mockery. “But mom, you forgot to tell me how you fell in love with my dad”. Kate looked up, looked at her daughter, and they both started laughing. And they realized that the laughter was heard louder, the noise from the street had almost disappeared. Kate and Rose continued working amidst laughter and memories with the “traca-traca” of the sewing machine.

Tick, tock, tick, tock.

Rosalba Esquivel Cote

She is a woman, Mexican, microbiologist, teacher, apprentice, and artist. “Let your cries be read!”

Selected Works by Aura R. Cruz Aburto:

La máquina de coser de mamá (II)

La Máquina De Coser De Mamá (I)

Mi Amiga y La Medusa

Otoño