Por Leticia Roa Nixon

Click here for English version

Las hermanas Nikté, Yamil y Muyal escuchaban con atención a su abuela, Balanca, “Nueve Estrellas”, quien les enseñaba los símbolos de los tejidos. El pueblo tzotzil de origen maya transmitía sus conocimientos a través de la palabra hablada para mantener viva su cultura y memoria colectiva. Sentadas frente a sus telares en su comunidad Venustiano Carranza del estado mexicano de Chiapas aprenden los símbolos principales que han usado los pueblos tzotziles de la región para expresar su visión de la vida.

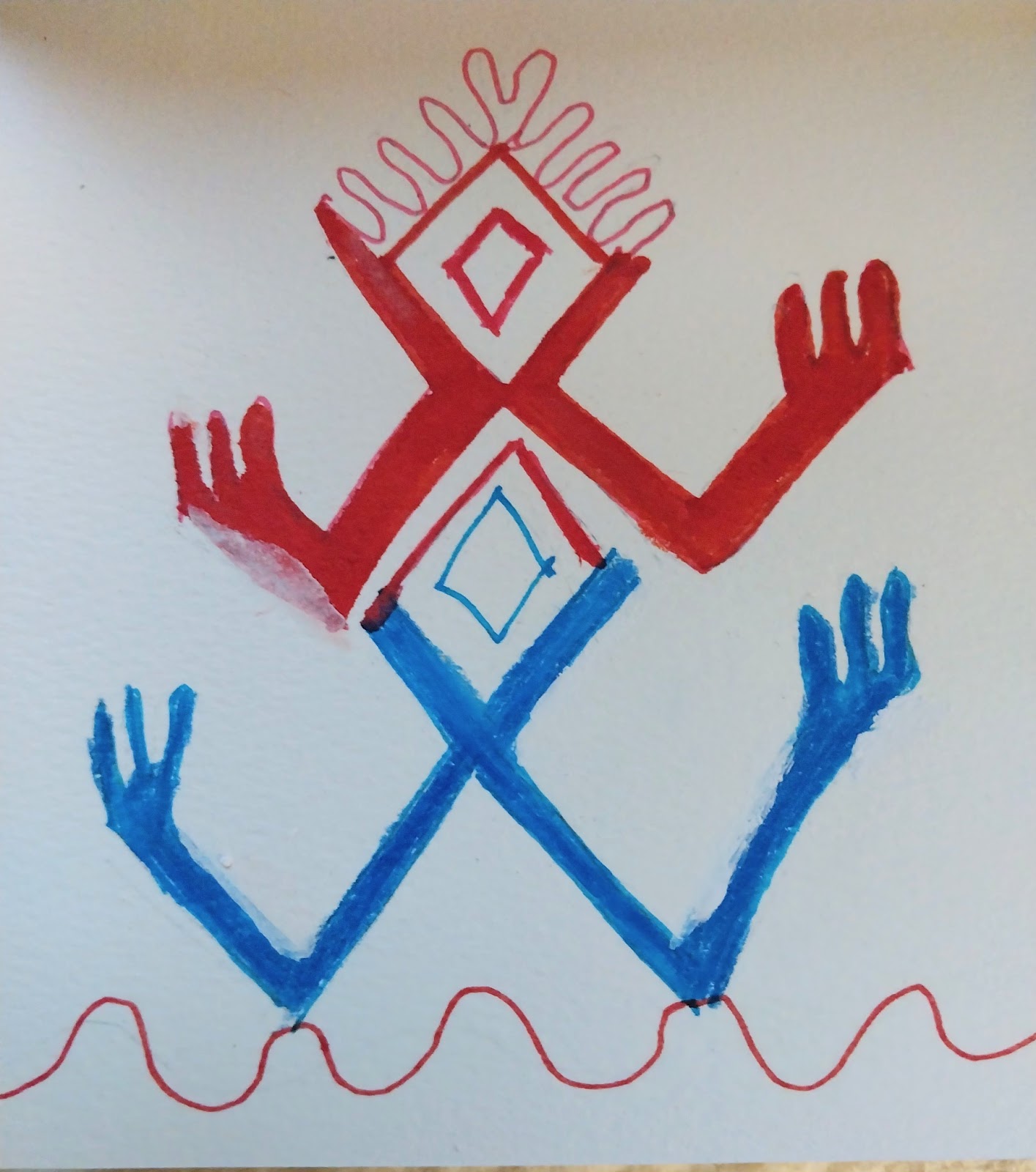

Así, es el rombo representa donde nace el sol, donde se oculta el sol, el corazón del cielo y el corazón de la tierra.El ixim representa al maíz. También hay un símbolo para la flor.

El sapo es un animal importante para las comunidades tzotziles y para otras muchas comunidades. Se asocia con el anuncio de la la lluvia tan necesaria para las cosechas.La mariposa se ilustra con figuras de rombos alineados sobre un eje. Estos ejes tienen forma de hélices a sus costados, en ambas direcciones.

En los bordados se pueden encontrar también figuras de animales como el quetzal, el pavo real, la guacamaya y el mono araña. En algunos tejidos también aparecen los árboles de ceiba el cual se considera el árbol de la vida para la cultura maya. Los colores verde, rojo, negro y azul también tienen un significado.

Las primas Itzamaray y Yamil también están ahí para apoyarlas. Las niñas han aprendido el bordado a mano y saben que se tardarán hasta 20 días para terminar el bordado su blusa.Esta actividad manual es una herencia tzotzil que suelen aprender las artesanas desde niñas, la mayoría de ellas a los 9 años ya saben bordar a mano.

La abuela Balanca usa el telar de cintura. Le ha enseñado a sus nietas cómo atar un lado del telar a un árbol o a un poste y el otro a la cintura para mantenerlo tenso con el peso de su cuerpo. Esta es una técnica prehispánica que se sigue usando y depende de la destreza de la tejedora que tan complejo es el diseño del textil.

El proceso consiste en entretejer los hilos de colores y crear brocados, para luego confeccionar una tela que posteriormente se bordará a mano, con flores y otros dibujos en punto de cruz.

Allí en las montañas chiapanecas, donde puedes casi tocar las nubes con tus manos, Nikté, Yamil y Muyal aprenden a contar los hilos, a levantarlos de trecho en trecho con la punta de un maguey, a combinar los colores y formar su diseño.Las niñas saben la importancia de aprender bien de su abuela pues algún día será su turno enseñarles a sus hijas. Además de conservar su historia, sus tejidos también serán una fuente de ingreso para sus familias.

Las tejedoras y tejedoras de los Altos de Chiapas saben que detrás de cada hilo están siglos de su historia que se ha conservado de generación en generación. Representan su mundo ya sea en un mantel, cojín, vestidos, rebozos, huipiles y caminos de mesa. ¡Qué orgullo poder lucir sus blusas y huipiles durante las fiestas de su comunidad! ¡Qué gran orgullo ser tzotziles y representar a su región en las ferias artesanales!

Ilustraciones y foto: Leticia Roa Nixon

English Version:

When Fabrics Speak

by Leticia Roa Nixon

The sisters Nikté, Yamil, and Muyal listened attentively to their grandmother, Balanca, “Nine Stars”, who taught them the symbols of weaving. The Tzotzil people of Mayan origin transmitted their knowledge through the spoken word to keep their culture and collective memory alive. Sitting in front of their looms in their community Venustiano Carranza in the Mexican state of Chiapas, they learn the main symbols used by the Tzotzil people of the region to express their vision of life.

Thus, the rhombus represents where the sun rises, where the sun sets, the heart of the sky and the heart of the earth, and the ixim represents corn. There is also a symbol for the flower.

The toad is an important animal for the Tzotzil communities and for many other communities. It is associated with the announcement of the rain so necessary for the harvests. The butterfly is illustrated with rhombus figures aligned on an axis. These shafts are shaped like propellers on their sides, in both directions.

Animal figures such as the quetzal, the peacock, the macaw, and the spider monkey can also be found in the embroidery. In some weavings also appear the ceiba tree which is considered the tree of life for the Mayan culture. The colors green, red, black, and blue also have a meaning.

Cousins Itzamaray and Yamil are also there to support them. The girls have learned hand embroidery and know that it will take them up to 20 days to finish embroidering their blouse. This manual activity is a Tzotzil heritage that the craftswomen usually learn as children, most of them at the age of 9 years old already know how to embroider by hand.

Grandmother Balanca uses the backstrap loom. She has taught her granddaughters how to tie one side of the loom to a tree or pole and the other to the waist to keep it taut with their body weight. This is a pre-Hispanic technique that is still used and it depends on the skill of the weaver how complex the design of the textile is.

The process consists of interweaving the colored threads and creating brocades, and then making a fabric that will later be embroidered by hand, with flowers and other cross-stitch designs.

There in the mountains of Chiapas, where you can almost touch the clouds with your hands, Nikté, Yamil, and Muyal learn to count the threads, to lift them from stretch to stretch with the tip of a maguey, to combine the colors and form their design. The girls know the importance of learning well from their grandmother because someday it will be their turn to teach their daughters. In addition to preserving their history, their weavings will also be a source of income for their families.

The weavers and weavers of the Chiapas Highlands know that behind each thread are centuries of their history that has been preserved from generation to generation. They represent their world in tablecloths, cushions, dresses, shawls, huipiles, and table runners, and are proud to wear their blouses and huipiles during community festivals, and to represent their region in craft fairs.

Illustrations and photo: Leticia Roa Nixon

Leticia Roa Nixon

Leticia Nixon, born in Mexico City, studied communications at the Universidad Iberoamericana. Since 1992 she has been dedicated to community journalism in Philadelphia. She is the author of six books and video producer for PhillyCAM. She writes for philatinos.com and lives in Swarthmore, Pa.

Selected Works by Leticia Nixon:

Berenice, La Danzante Azteca (Berenice, The Aztec Dancer)

Huracán Corazón Del Cielo (Huracán, Heart of the Sky)

El Lienzo de Tlapalli (The Tlapalli Canvas)

Leave a Reply