Por Pam Margolis

If you’ve ever had the pleasure of observing or interacting with children of any age, you’ll know they are driven by a moral code. This moral code may change from moment to moment and is often egocentric and situation specific. When boundaries are crossed you will hear the inevitable outburst “that’s not fair!” Sadly, children learn too young that the world is neither fair, equitable, nor free.

Children also know that helping others benefits both sides and that participation is an activity that can be rewarding. Yet while kids enjoy participatory events, they know the difference between voluntary and involuntary participation. Forcing kids to participate is not always a negative experience, however. Certainly, forcing your little one into the car seat when you ride in the car is different than forcing them to wear a tight, itchy, and uncomfortable outfit. Children’s lives are full of forced participation accompanied by silent threats, open harassment, and bribery. They are, perhaps rightly so, provided few opportunities to self-govern; they might choose eating sweets instead of vegetables, skip baths, and unintentionally play too rough with the cat. Experts have written extensively about children and participation. Kids know when their participation is manipulative and/or when participation is a collective decision.

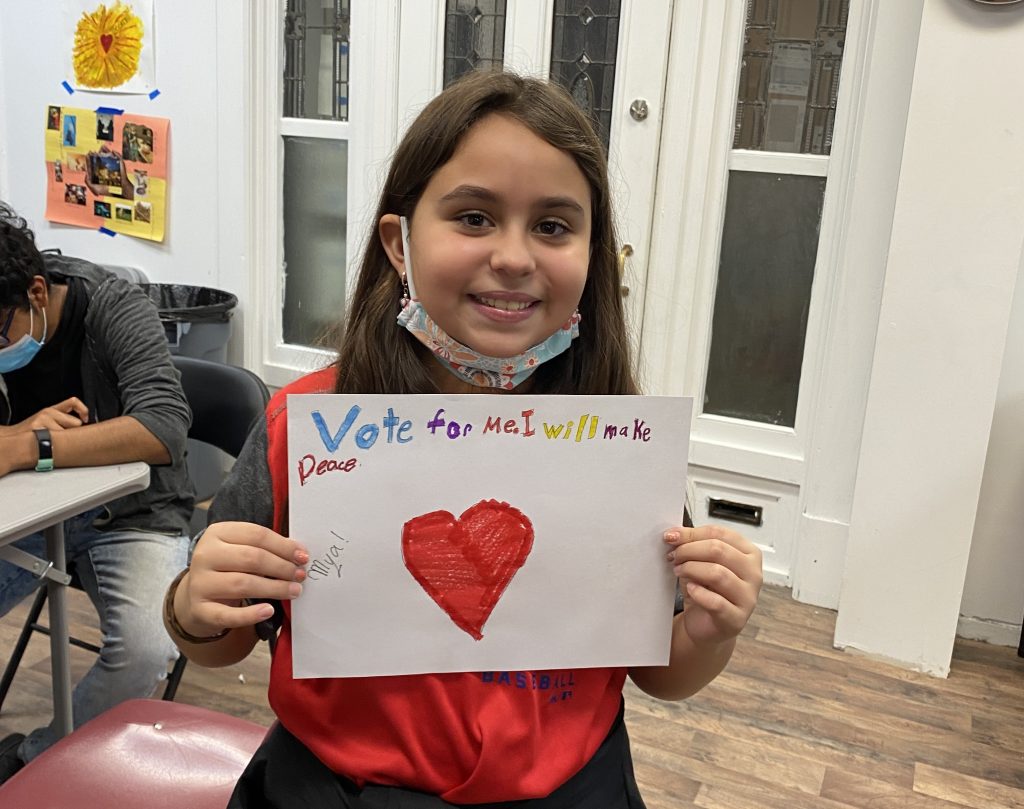

Given all that children know, why don’t we give them more opportunity to choose the particulars of their participation? After all, participation is supposedly a necessary part of democracy. Why not provide children with more opportunities to practice democracy? I don’t always get it right but my goal in developing the Finding Your Voice class was to engage kids in true deliberative and participatory activities. Great thought and research have gone into my methodology: it is infused by Freire, Black Feminism, critical race theory, and LatCrit. I value the expertise, experiences, and opinions the kids at CCATE bring to class. By providing opportunities to share their knowledge of their lived experiences we are creating a tiny equitable democracy.

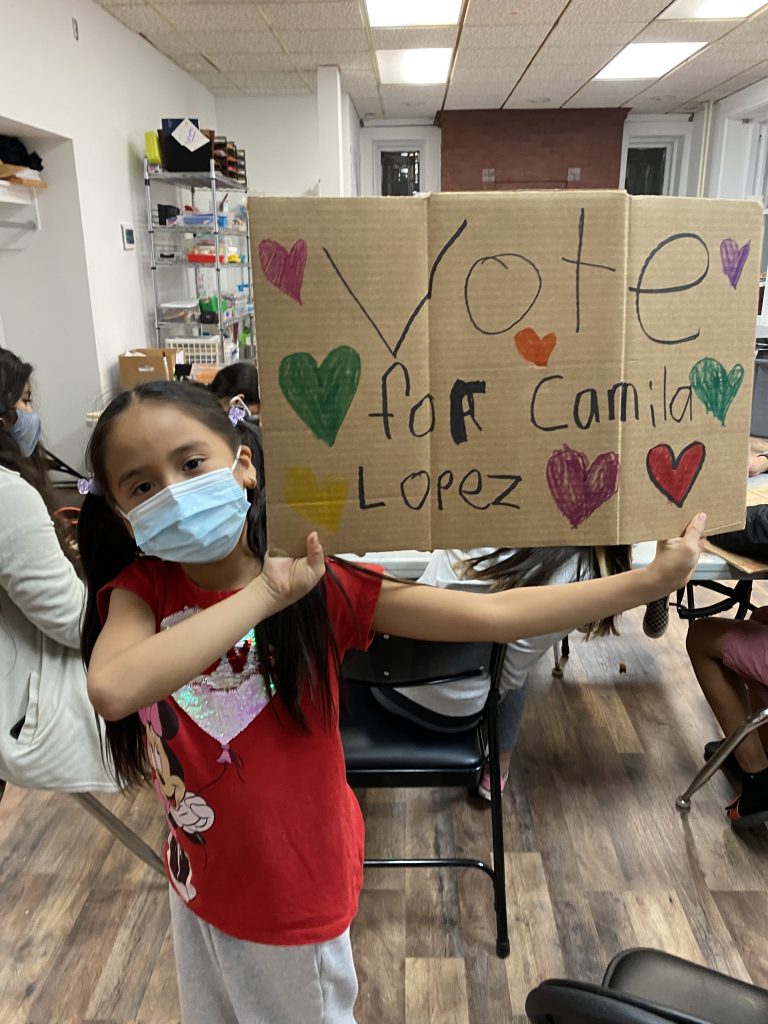

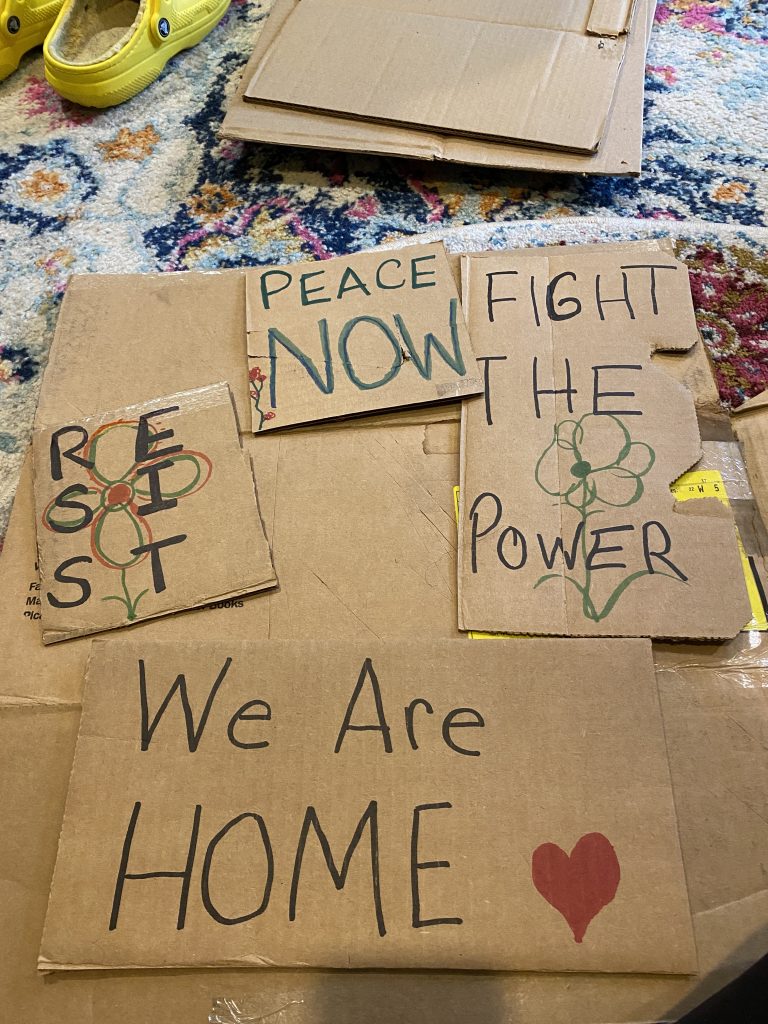

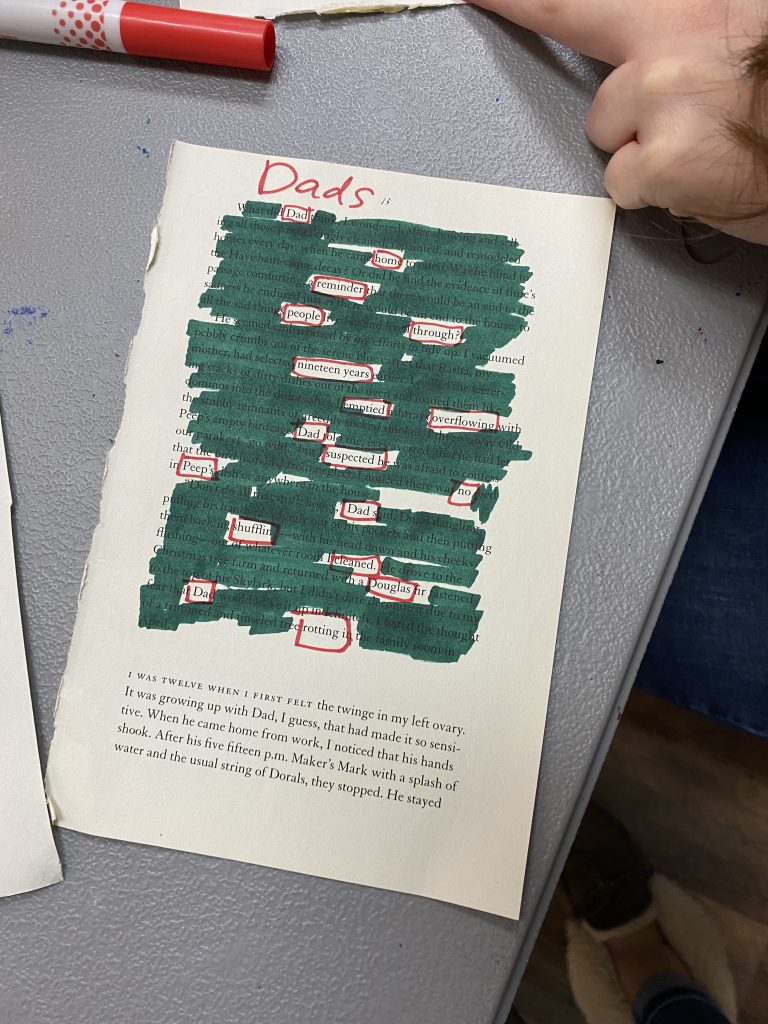

Finding Your Voice provides opportunities for the kids to tell their stories in various formats: drawing, poetry, in Spanish or English, as a storyboard, a ‘zine, acrostic poem, or even as a protest sign. During Finding Your Voice, we don’t correct their spelling and grammar, however, we will help them if they ask. These kids are critiqued and disempowered enough during the day; they don’t need more of that. I believe critique slows the creative process and is another barrier to success, another way for the students to internalize negative feelings. The class is at its best when students are talking, singing, moving from table to table sharing ideas, resources, and enjoying the creative process. In class, the kids may see Caitlin and me as maestras, but I see us as facilitators of democracy. In the hour they are with us, the world is free, equitable, and fair. We are building the world we want to see.

Pam Margolis

Pam Margolis is a doctoral student at West Chester University studying curriculum and instruction. She is passionate about equity in education for children from marginalized groups: African American, Latinx, disabilities and LGBTQ. She is an expert in the curation, development, and expansion of curriculum and library resources representing children from marginalized communities. Pam has an Executive Master of Public Service from the University of Arkansas Clinton School of Public Service, a Master’s in Library and Information Science from Drexel University, a BS in English Writing and post baccalaureate in Teacher education, as well as K-6 Elementary Education certification and K-12 Library Media Specialist. Committed to the marriage of civic engagement and education, Pam serves her community as Perkiomen Township Supervisor.